6th November 2023

Listen

Listen

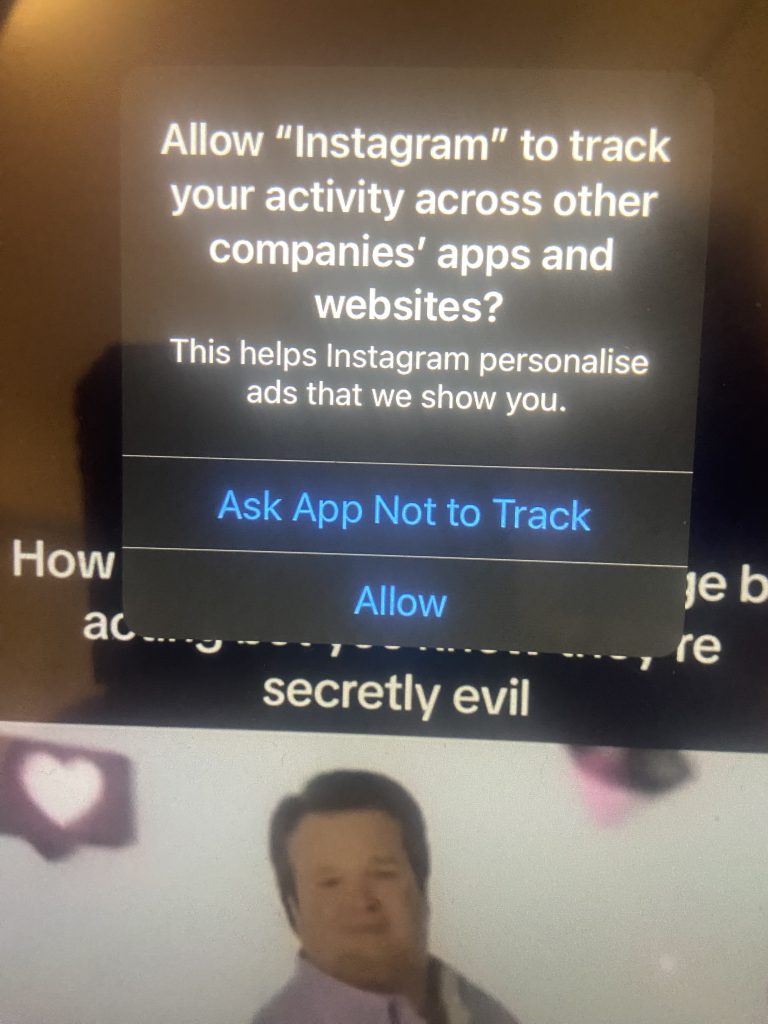

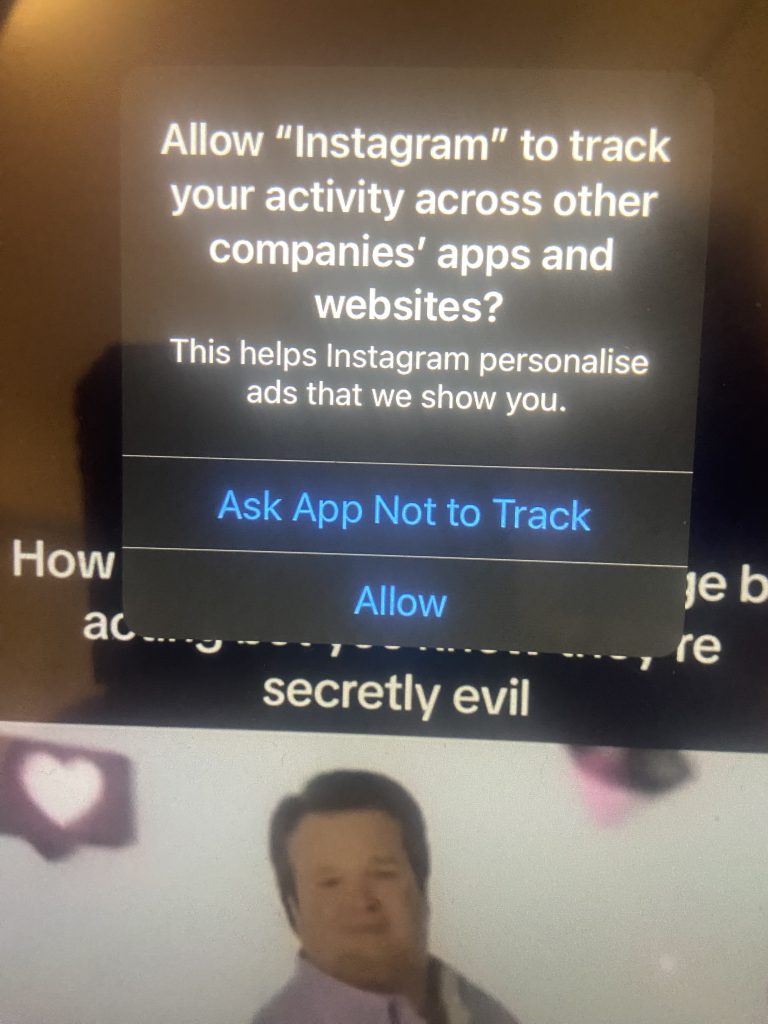

Recently, I have been using apps like Instagram, Trainline and TikTok as part of my typical routine. In doing so, the following message has been cropping up on countless occasions:

This may appear to be like regular procedures being carried out by Apple (we ignore the creeping presence of Modern Family‘s Cameron Tucker, a show which I still need to watch). However, App Tracking Transparency was something which began implementation following on from Apple’s 14.5 OS version (which released on April 26th 2021).

My iPhone 11 is on iOS 18.5, but why am I only receiving these requests now rather than a few years ago? Why is there now the sudden concern for users’ rights to their personal data? To examine this, I checked out the Apple Support page, with the company publishing a blog on December 29th, 2025.

Disclaimer: I am not an advanced programmer or computer scientist. Just a concerned writer with a Computer Science and Media background, worried about how exactly our data is being handled.

These requests seem to come through via Settings > Privacy & Security > Tracking > Allow Apps to Request to Track, a feature which seems to have automatically enabled itself, as I hadn’t manually turned this on.

Apple lists several reasons for why this setting may be unavailable:

These are the following apps which have asked for permission to track my activity:

Additionally, why is the top option labelled as “Ask App Not to Track” rather than “Not allow”? The lexis does almost insinuate that our compliance relies on trusting the developer’s honesty.

Does this imply a risk that some apps won’t respect an individual’s privacy? How can we be sure Apple will do everything in its power to avoid this situation?

According to Apple, apps tracking your activity allows consumers to decide if they would like companies to monitor their habits, done so by cross-referencing other company apps and websites. They define this form of tracking as occurring when “information that identifies you or your device collected from an app is linked to information…collected on apps, websites and other locations owned by third parties for the purposes of targeted advertising or advertising measurement, or when the information is shared with data brokers (a company/individual specialised in collecting personal user data)”.

In other words, they track you through the information you generate from app engagement, which third-parties harvest to push ‘personalised’ advertisements or to obtain people’s data. The behaviour you present in the app becomes commodified.

Let us go through the scenario of App Tracking Transparency: when you open an app, you may potentially receive a pop-up notification request asking to track your activity. This doesn’t affect the app’s functionality, but it does restrict what data the developers can access.

If the developers don’t customise the message to explain the need for tracking, you can check the app’s product page within the App Store. This will offer more information on how its developer uses your data.

If you click the button “Ask App Not to Track”, the app’s developer cannot access Apple’s system advertising identifier, known as IDFA. This is a unique, user-resettable key which allows for third-party tracking to be carried out on mobile Apple devices.

For tech fanatics out there, IDFA is an “alphanumeric string that’s unique to each [Apple] device…only use[d] for advertising”. Android’s OS has a similar system advertising identifier known as Google Advertising ID, or GAID.

Once this request is denied, the app cannot track your activity using other identifiable information, such as your email.

I will use Instagram as our app for this scenario, since the screenshot above was taken from it. When scrolling down on the App Store, the platform’s privacy section contained the following:

As you can see, that is a lot of attributes related to you, which are regularly surveyed, assessed and updated. Each app will have its own privacy policy, as online or ‘new’ media (as it’s referred to academically) isn’t regulated in the same sense as other mediums (e.g – IPSO with print industry, Ofcom with TV and radio). This is due to its broader and more erratic nature (such as the dark web, anti-fandom, etc).

Attempts to regulate digital media have certainly been made, such as Professor Tanya Byron’s 2008 report, which contained 38 recommendations on how to keep children safe online. Some succeeded, such as parental controls, ISP-level filtering and advertising regulation, whilst others failed or remain incomplete (such as voluntary industry codes and moderation standards).

Online regulation seems to always be far more challenging than other mediums.

(The following information is taken from my COMM109 lecture notes)

We must consider what companies have to gain from this ability to effectively gather and weaponise data. Well, firstly, the ease at which this comes for them is possible when living in a world of surveillance capitalism – a term coined by Harvard economist Shoshana Zuboff that defines an economic system where private tech companies collect, extract and employ user’s personal data. They do so to obtain profit and power by predicting and influencing potential monetisation strategies (e.g – targeted ads, app personalisation, product development, behavioural influence).

Secondly, you may be wondering how exactly these companies embody this system:

Companies have everything to gain from this. They are able to satisfy their own personalised agendas through the supervised seizure of our data. They scour for it, they find it and then they endorse it to prospective shareholders.

A good case study to consider is former privacy commissioner Daniel Therrien’s 2021 report for Canadian citizens about surveillance capitalism, discussing how privacy has entered a fragile state. This is due to tech giants like Facebook and Google “seem[ing] to know more about us than we know about ourselves”. He asserts that surveillance capitalism has taken “centre stage”, with people’s personal data becoming a “dominant and valuable asset” via these digital corporations leveraging it “behind our web searches and social media accounts”.

He references the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica controversy, which is where Facebook was sued in October 2020 for unsuccessfully protecting users’ data from a breach; this resulted in 87 million people’s data being harvested for use in advertisements during elections. The incident reflects the necessity for prevention methods, such as penetration testing – this is where system vulnerabilities are tested and flaws are fixed.

This case was carried out by the group Facebook You Owe Us, disputing that acquiring user data without expressed permission violated the legislation of the 1998 Data Protection Act.

According to what I learnt in Computer Science, the Data Protection Act ensures data is lawfully and fairly processed, relevant, accurate, secure and not kept longer than necessary. Another important piece of legislation you should be conscious of is the Freedom of Information Act, which gives people (or data subjects) access to information held by organisations that revolves around them.

Therrien’s frustrations with the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica case was that not only was surveillance capitalism at its most obvious, but that his office “did not have the power to order Facebook to comply with [their] findings and recommendations, nor issue financial penalties to dissuade this kind of corporate behaviour”. This does reflect Livingstone and Lunt’s theory of media regulation, in the sense that big companies can evade regulatory guidelines.

(The following information can be accredited quite a bit to my COMM101 and COMM109 notes, alongside gained knowledge)

This constant controlled surveillance of who we are as individuals does seem to reflect a psychological impact of being constantly monitored. Particularly, Michel Foucault’s concept of panopticism.

In his 1973 piece Truth and Juridical Forms, he declares that panopticism is:

“a type of power that is applied to individuals in the form of continuous individual supervision, in the form of control, punishment, and compensation, and in the form of correction, that is, the modelling and transforming of individuals in terms of certain norms. This threefold aspect of panopticism – supervision, control, correction – seems to be a fundamental and characteristic dimension of the power relations that exist in our society.”

Citation:

Michel Foucault, (2000) [1981] ‘Truth and juridical forms’. In J. Faubion (ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Power The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. Volume Three. New York: New Press, p. 70.

Historically, the panopticon was a circular prison with cells arranged around a central well, allowing prisoners to be observed at all times. Nowadays, this structure adopts a more figurative portrayal and hides itself within both the physical and digital realms.

Academically, it acts as a lens to embrace the sociological imagination, a phrase coined by American author C. Wright Hills within his titular 1959 book; this term in my opinion defines a perspective shift from our own personal routines to evaluating the things we engage with and abide by in society.

ReviseSociology’s example is a sociological investigation into coffee, which reveals its symbolic value as being a frequent part of people’s morning activities; it also acts as a cataylst for social interaction.

Within a panoptic framework, members of society self-regulate themselves, internalising the panoptic gaze and modifying their behaviour to conform to the status quo. Deeply embedded are invisible power dynamics which operate throughout societal institutions (e.g – education, media, family). The watcher – society in this case – holds this dominance through its camouflage and the watched – individuals – are constantly exposed and judged.

Society is the panopticon.

If we apply this to the topic of the article, data brokers and third-party companies are keeping us aligned with their commercial imperatives. Once we learn of their intentions, we self-regulate ourselves to remain in accordance with societal norms. In fact, we already do when we adhere to the app’s User Agreements, where we promise to behave in a diplomatic and responsible manner.

This already establishes an unequal footing, where we as users are at the mercy of these companies’ platforms in order to sustain connectivity with friends, family and society.

While there are ‘faces’ behind these big corporations – such as Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg – they and the people working within this often remain obscured from the majority of the public, hidden behind the brand identity. Think about it. We all use apps like Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. But odds are many of us don’t know the production process of these applications, retaining a surface-level comprehension.

If I asked you who founded Instagram, would you know? The answer is Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger in 2010. What about how many employees? Not that many, with it only having 13 employees when it was sold for $1 billion to Facebook in 2012.

This small proportion of employees is due to automated processing, with programmers developing algorithms that self-operate content and services. The acquisition also reflects the underlying logic of monopolisation – a company intending to own a large portion of a market: buy out competitors, merge or cut your losses.

Sure, now you know. But I imagine most of you were unaware of this.

Let me ask you another question. How are these companies funded? Well, it comes down to 3 primary means:

Some major social media platforms generate barely any revenue (e.g – LinkedIn was bought by Microsoft in 2016 for $26.2 billion, a year after LinkedIn’s $165 million loss; Microsoft had acquired LinkedIn due to the large quantity of data, encompassing around 800 million (mostly) professional people.

Our activities generate these huge sums of data that are fed into algorithms to perpetuate this participation loop. As such, this infinite regress positions people as more so the result of social media platforms, rather than being the users or ‘consumers’ themselves.

Your online activity is documented. Your digital footprint begins and amplifies the more you partake in the digital realm. Now, this isn’t me trying to discourage you. But simply advising you on the baggage that is carried with it.

This is why that pop-up message from Apple worried me. Because if these companies can track what I’m up to, of course that’s amazing in that it gives me more personalised advertisements. But it renders my autonomy and agency null and void, with companies more concerned with the data I create than my own personal interests, raising the cultural issue of invasive technologies.

I believe we are no longer individuals but what French philosopher Gilles Deleuze in Postscript on the Societies of Control calls ‘dividuals’; this is where people are addressed only for the data they create online, rather than their identities and individuality.

It promotes an apathetic and unforgiving climate, one which we should strive to change.

We should be cautious with our online personas and resist any attempts to steal the data we are intrinsically responsible for.

Any questions? What do you believe about online media and our data? Are we exploited or empowered? Feel free to contact me via johnjoyce4535@gmail.com!

Check out my last piece: Archived Fluency: Deconstructing Corpus Linguistics

For more opinion pieces, check out the following link:

https://www.liverpoolguildstudentmedia.co.uk/category/opinion