6th November 2023

Listen

Listen

As referenced before in some of my articles, my long-term goal has been to become a journalist. I suppose in a sense I am now, since my role is to adopt Reithian philosophy. That is the trinity of informing, educating and entertaining you as readers. According to University of Sussex professor David Hendy, Reithianism in its conception was concerned with “looking to the future”; to him, it was:

Rather, he believed that it “needed to imagine other ways of being in the world”.

Disclaimer: This article is a two-parter. The first article began looking at the history of media & communication, linked here. This second article will investigate journalism.

Everyone can be a journalist to some degree, since it never has truly been a field with special requirements, but it does require consistency, motivation and developing a specialism. Many people like myself who want to delve into a world such as this will pursue a degree within a relevant subject – such as Journalism, Media & Communications, English, History, Law, etc.

My original plan was to study English at University of Oxford and then complete an NCTJ course within my own time; however, now I am studying BA Media, Data and Society at University of Liverpool. Moreover, some individuals will even specialise via a masters to enhance their employability, in pursuit of high-level roles or niche reporting.

The most direct path for being deemed an officially qualified UK journalist is to partake in an NCTJ-accredited course. The NCTJ (National Council for the Training of Journalists) is the British media’s organisation which “delivers industry standard qualifications for pre-entry and trainee journalists, as well as professional qualifications for working journalists”. They are regulated by Ofqual, CCEA and Qualifications Wales.

But like I said, anyone can be a journalist. Having the ability to write, research and navigate digital realms is an essential commodity for anyone. Digital media has made it where citizen journalism is at the forefront, using our phones as activist and alternative expression to capture and reflect the news. In 2014, professor of journalism in the University of Georgia Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication William E. Lee stated that “Anyone can be a journalist and they don’t need an affiliation with an established outlet”. This idea was published in an article within the Georgia Law Review.

The thing that appeals to me so much about journalism is having the chance to write about something you and other people are passionate about, while also being able to learn and teach readers new information and insights. These two aspects of journalism reflect its two forms: representative and educational ideals, terms taken from Mark Hampton’s book Visions of the Press in Britain, 1850-1950; journalism originally began as playing an educational role for the public, until it became more renowned for catering to tastes and interests, producing media sensationalism.

To understand the history of journalism, we need a good understanding of how media and communication came to fruition. I would recommend you checking out this part of my previous article, where I produced a timeline considering the historical context.

For this article, I will focus on journalism in its own right, while of course accounting for the crossover. I am using Thomas Birkner’s section about the History of Journalism within Europe. This is taken from the Handbook of Media and Communication Economics: A European Perspective.

Thus, this won’t cover every crucial part of journalism’s history but serve as a general summary.

Despite Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, mass media wasn’t truly invented. You may wonder why that is. Well, his invention was partly used for the aesthetic rather than functional purpose of book-copying. That was, until bookbinder and news dealer Johann Carolus acquired his own printing press.

In doing so, he merged news and printing to invent the newspaper Relation in 1605, with newspapers becoming the first mass medium.

He published Relation weekly, standardising built-in obsolescence (the deliberate short-term consumption of media texts to ensure repeated engagement). Carolus also pioneered letterpress printing, due to the time-consuming nature of written news reporting.

Since this was the first instance of journalism, modern tropes such as newsrooms, established journalists and defined news formats weren’t present and so this delivery of information was non-professional. Regardless, Carolus was economically interested in maximising revenue through achieving high circulation and sales. Successors appeared shortly after, such as 1609’s Aviso in Wolfenbüttel.

War has a habit of perpetuating news, since people rely on information as a means of reinforcing hope and their will to keep pushing on. This was evident during the 30 Years’ War (which took place between 1618-1648), via the first Netherlands newspaper in 1618, France in 1631 and Sweden in 1645. In fact, the Post- och Inrikes Tidningen – the first Swedish newspaper – was the “oldest newspaper in the world” (Hatje, 2008, p.210), which stayed in publication until 2007.

According to Raabe – cited in Brosius and Jarren’s Lexicon of Communication & Media Studies – there are 4 characteristics fundamental to that of the newspaper: topicality, periodicity, publicity and universality (p.322-324). These were developed in response to the publication of the first daily newspaper in Leipzig called Einkommende Zeitungen, published in 1650.

Due to the lack of effective long-distance communication channels, the transmission between an event occurring and the news reporting it was asynchronous. Daily journalism couldn’t be truly carried out in a world prohibited by its technological constraints.

Moreover, news was unstructured and lacked any form of credible opinion; this was partly due to censorship limits but also due to educational limits, as those who worked to produce the newspapers weren’t as qualified as the few educated readers during the time. This of course has changed in the last few centuries but due to it being a new phenomenon, it was merely a case of trial and error.

Within Europe, there was a large absence of what we know as freedom of the press (right to publish and share information without censoring and/or government interference), so writers and pre-journalist figures such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Heinrich Heine popularised political essay writing; these would initially start off as part of the weekly publications, until emerging in the daily press and forming a new journalistic genre. This would serve as a counterpart to traditional news formatting.

Journalism still remained a role which faced immense censorship. Newspapers were confined to governmental restrictions, with the Frankfurter Zeitung proposing 3 ‘Cs’ that made running a newspaper incredibly challenging during this period: Conzession, Caution, Confiskation. High deposits had to be paid for the opportunity of sharing news, whilst police were able to confiscate press products. Despite these obstacles, journalistic developments slowly continued.

Institutionally, an editorial office spawned, with news gathering on one side and printing and publishing on the other. Journalism’s forms and styles began to become more distinct, with news following the chronology of events rather than “a journalistically formulated dramaturgy“. In other words, news was becoming less dramatised and taking a realism approach. There were 3 journalistic institutions until the mid-19th Century: feature, news and editorial.

Journalism changed its linguistic approach through the genre of reportage (first-hand/commentary of an event) and editorials (article expressing an editor’s opinion on an issue). This led to the formation of the opinion press. Kurt Koszyk (1966, p.128) discusses an “epoch of the political party press”, with Horst Pöttker (2005, p.144) defining this via:

“Since German journalists were only freed from the shackle of censorship comparatively very late, the desire to gain publicity for one’s own convictions was set that much more intensively in motion. The German tradition of political partisan journalism since the mid-nineteenth century can, as a consequence, be interpreted entirely as an overdue and thus more intensive fulfillment of a long-obstructed need.”

We can interpret this biased journalism as almost a form of catharsis, with German journalists incredibly resentful of the oppression they received regarding their work pre-1848. Another part Pöttker mentions is that of political journalism. Whether we care to admit or not, everything is political. When it comes to society, we cannot escape political influence. Particularly with the media’s explicit (e.g – coverage of politician debates) or implicit (e.g – the media we consume; political themes) focus on the subject.

Birkner states that journalism remains a part of the political system during this time because often the party’s newspapers are formed first, which result in official political parties (pg.1000). The news establish political ideologies, which individuals follow through with by officialising the ideology.

When we consider the next step of journalism, we need to take a look at society. Specifically, some key social trends during the German Empire. That is population growth, which connects to urbanisation and literacy rates. The ratio of rural-urban population reversed; at the Empire’s start, 60% of the population lived in the countryside. By 1910, 60% of Germans lived within cities (Wehler, 1955, p.512).

Next, in 1871, Prussia had defined 12% of its population as illiterate. By 1899, this was only 1% (Engelseng, 1973, p.98). Despite this physical transformation, journalists needed a way to navigate urban and rural communication space. They needed a uniform legal framework. This was done via the 1874 Imperial Press Law, which offered some semblance of freedom of the press. Although this freedom wasn’t universally shared, the framework was functional and led to a press boom.

Because of this law, newspapers became commercialised, developed as mass products and tapping into different audience strands. In stating so, we can claim that this is a process of democratisation. Towards the end of the 18th Century, newspapers and magazines experienced an industrial diversification non-existent up to that point.

We also saw an arrival of advertising financing, with the start of the 20th Century highlighting that approximately 66% of advertising’s total revenue stemmed from daily newspapers.

It is a fair claim to make that modern journalism began at the start of the 20th Century. At that time, “around 120 daily newspapers” appeared within Switzerland (Meier, 2005, p.423). Journalism filters into several aspects of society and culture, such as the economy, technology, politics and law.

New, prominent features were beginning to be created that would lay the foundation for the principles of modern journalism. For instance, its own press economy, which functioned through its leaning towards mass production and extremely high first-copy (replicas of official products) costs. In other words, the prominent dissemination of copycat brands.

Newspapers had also began to classify its own conventions, with the beginning of the 20th Century containing the following traits:

Newspaper’s contents were produced by professional journalists, which are from both employed and freelance backgrounds. Paul Stoklossa during the years 1904-1908 had evaluated job offers and applications for journalism employment within journals (Stoklossa, 1910, p.532):

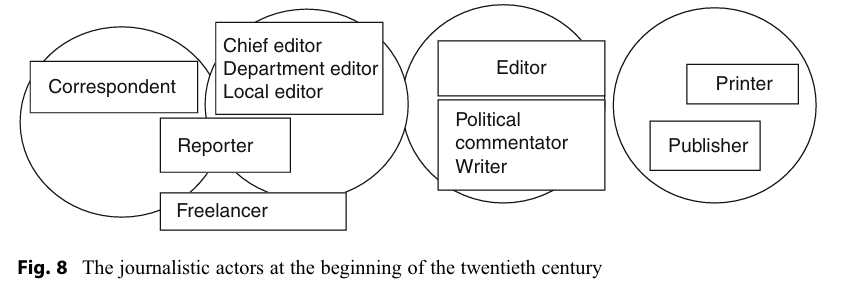

This is visually how journalistic groups acted within the start of the 20th Century:

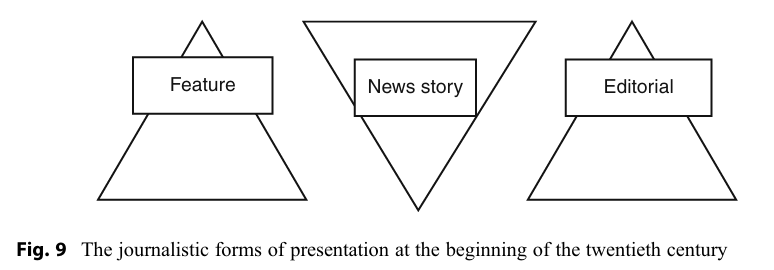

We must also consider how journalists structure the importance of news texts, using Birkner’s hierarchically structured pyramids:

The middle triangle is a common concept within journalism, known as the Inverted Journalism Pyramid. In summary, it is a visual method of organising news stories from most important to least important; this enables readers to discover the key details immediately and offer some organisation to a writer’s work.

It adheres to the following structure:

Once WW1 began, freedom of the press’s enforcement ceased to exist, due to military censorship and propaganda. So too did advertising revenues, with economic interests pivoting towards the wartime crisis. Despite German journalism flourishing post-1848, it found itself once again trapped under political duress. Under National Socialism, the discipline found itself as a “völkisch“ observer; this word translates to populism as an attempt to reinforce German superiority, however this ideological form contained a racial stigma.

When radio was developed – entering Germany, Austria and Switzerland around the same time at the start of the 1920s – Joseph Goebbels weaponised the medium as a propaganda tool in 1933. Once WW2 ended, the Allies reorganised the West German media system and decentralised broadcasting. However, initial fears of print media redundancy began, in part due to the introduction of TV.

Within West Germany, Austria and Switzerland, TV started off through a PSB (Public Service Broadcasting) structure. Despite this, discourse surrounding broadcasting strategies continued on throughout the decades and the growing fears of failing print media circulation only became worse.

Advertising also began to fail in financing journalism, since many adverts are choosing digital integration over physical presences. The Internet has made print journalism content almost extinct, since online journalism is largely free to access (like this article here). The struggle for profit is an enormous issue which pervades modern journalism.

Within the history of journalism, there is one term I would like to consider: information revolutions. Coined by Irving Fang, these are calls to action regarding the presenting and sharing of information, with this causing profound societal changes. According to Fang, a successful information revolution requires the development and sharing of new media technology, which must be happening during a changing society. The media supports and is amplified by events that challenge the status quo, as reformers need a platform to vocalise their opinions.

So, what exactly is the criteria for an information revolution?

Fang goes on to say that there are six periods within Western history which fit into his criteria of an information revolution:

We are supposedly within the Information Age, however media scholars debate on what part of history consists of this period; Fang is adamant that the second half of the 15th Century/1400s has a strong claim to be called the Information Age, due to Gutenberg inventing the printing press. Many believe that the second half of the 19th Century/1800s fits this, following the inventions of photography, the telegraph, phonograph, telephone, typewriter, motion pictures and radio.

This is alongside key printing changes and early TV & recording tape experiments. While he does remark that changes within communication transpired during quieter periods, the ones referenced hold a greater significance.

Journalism in my opinion is incredibly important to how we function as a society. It is found within all aspects of culture besides politics. An art form which we use to communicate and comprehend ideas, be it for educational and/or entertaining purposes. We as members of society use it to sustain connections with the world around us, keeping updated on current events and figures.

But it’s not just a tool for information. It can be a weapon, a catalyst for exposing wrongdoings and corruption (the extent to which it does this of course depends, due to risk of sensationalism). For example, the News of the World phone hacking scandal. We use it as a vessel for factual storytelling, sharing the experiences of anyone and everyone.

In the past, the media has triggered a symbolic annihilation – a term coined by Gaye Tuchman initially relating to women – of key societal groups, such as women, ethnic minorities and disabled people. However, each day, it arguably rectifies this behaviour by amplifying these silenced voices.

While lots of the media does in my opinion have the power to manipulate people’s thinking, we as individuals have an unspoken responsibility to think critically and determine our own viewpoints. To do so, we consider multiple perspectives and constantly re-evaluate our stances when new information is presented to us. We revel in media literacy.

In this current climate, we arguably live in a media democracy, with the media often serving as a platform for reform and expression.

Any questions? Feel free to contact me on johnjoyce4535@gmail.com!

Check out my last piece: Literary Upload – The History of Media & Communication

Or why not check out my new website! I have published a blog called Linguistics: 101, serving as an introduction to linguistics.

For more on arts & culture, click the following link:

https://www.liverpoolguildstudentmedia.co.uk/category/arts-culture